Everything dances

Images in the archive of the UCT School of Dance

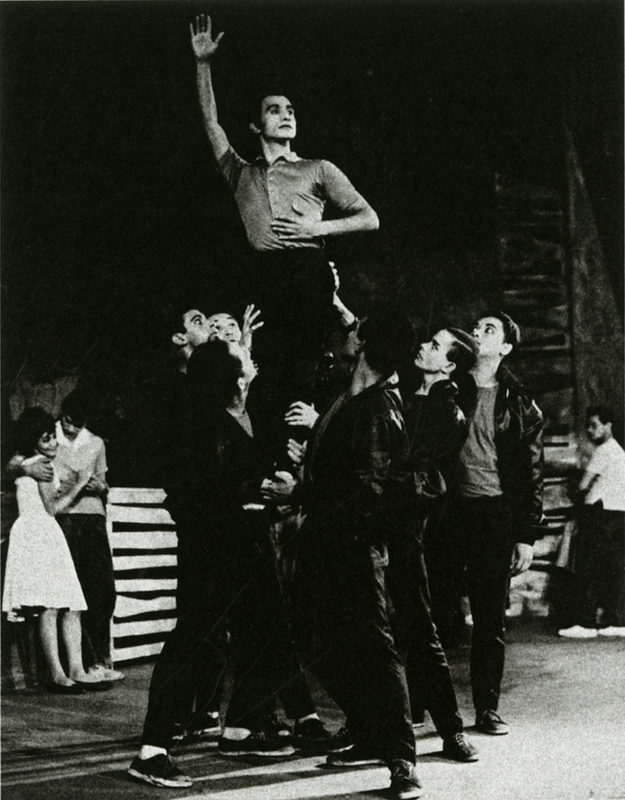

UCT School of Dance’s evolving archive houses thousands of photographs, recordings and other artefacts that capture the history of a school and company in motion since 1934.

Moving through the spaces and offices of the School of Dance, when I became Director in 2008, I unearthed boxes containing collections of old photographs, posters and programmes that go back as far as the 1930s. I discovered that, despite its long heritage, there was no formal dance archive for the School, and I was very eager to start that process.

The School of Dance was founded under the aegis of the SA College of Music by Dulcie Howes, who had danced in [Russian prima ballerina] Anna Pavlova’s company. It was 1934 and the aftermath of World War I was still lingering across the globe. The studios were set up in a disused aeroplane hangar.

‘I’ve found rare photographs of Margot Fonteyn that are sitting here. These 500 photographs are the absolute tip of the iceberg. The material we have is gold.’

At that stage, the University Ballet – which became CAPAB and later the Cape Town City Ballet – was conjoined to the School of Dance. The current buildings were designed by acclaimed architect Revel Fox in the early Seventies, but it was on this very site that the University Ballet produced, over the years, thousands of dances. We were a feeder school to the Royal Ballet in London, and at some stages in the School’s history, over sixty percent of those dancers actually came from here.

In addition to programmes, costume sketches, video recordings and interviews, there are more than 3 000, largely black and white, photographs in the collection. I’ve found rare photographs of Margot Fonteyn that are sitting here. These 500 photographs are the absolute tip of the iceberg. The material we have is gold.

The digitisation of these first 500 images is the initial step in a much bigger archive project. What we’re hoping to achieve via Humanitec is to generate excitement among the wider research community about the amazing source material that we have available here. I mean, you might have someone who is studying World War II, who might specifically want to look at how the troops were supported and entertained? This needs to be a research space that they could come to.

There are all these cross-disciplinary links. I’ve discovered, via our music librarian, Julie Strauss, that we have an extraordinary collection of photographs by Anne Fischer. PhDs have already been written about Fisher’s photography and her particular eye, and we are sitting with her original signed photographs.

‘The Ballet Company was so celebrated that a bit of a blind eye was turned to the fact that these coloured and white dancers were working together in intimate bodily contact… That whole history is, as yet, untapped – it’s been too painful maybe. But I feel we’re now at a juncture where it is ready to enter the public domain.’

We also have things like technical sketches that led to the costume designs for the lead dancers of seminal productions. Over time, these designs have become very valuable. Only recently, I was paging through a 1940s scrapbook and out fell an original drawing by the artist, John Dronsfield, who was very much part of this dance community.

There is also the enormous issue of South Africa’s racial past in terms of dance –how to honour people’s stories – because this was a space that took enormous risks in including dancers of colour well before any of the democratic changes in the 1990s. Dulcie bravely flouted the law and the so-called ‘white’ Ballet Company had large numbers of coloured dancers as far back as the ’60s and ’70s. I come from an Indian family and I trained here in the ’80s. The dance fraternity was ahead of the rest of the country.

Despite the laws of the time, nobody was ever arrested here at the School for being in a mixed company. The Ballet Company was so celebrated that a bit of a blind eye was turned to the fact that these coloured and white dancers were working together in intimate bodily contact. And, of course, gender studies could have a field day looking at this material. That whole history is, as yet, untapped. It’s been too painful maybe. But I feel we’re now at a juncture where it is ready to enter the public domain.

Who knows the stories of the first so-called Coloured dancers in our country? Who has the recording of the first black African dancer in our city? It’s all of these stories that still need to be told. There’s wonderful information here and we are growing the generation of people who can now articulate these stories in terms of writing articles, journals, monographs, books… This archive is an attempt to get some of our stories, our history, into circulation.

‘There’s wonderful information here and we are growing the generation of people who can now articulate these stories in terms of writing articles, journals, monographs, books… This archive is an attempt to get some of our stories, our history, into circulation.’

Ideally, I want researchers from all over the world to be able to come to Cape Town. If they are studying any aspect of the development of British Ballet, for example, they could come here to explore the South African connection. So many dancers who were trained here became famous in London, Europe, the rest of the world.

In my travels, presenting papers at conferences, I have, for example, come across a dance historian who is looking at an artist called Yvonne Mounsey. The global dance community knows her as the most celebrated ballerina with [George] Balanchine, [one of the 20th century’s most prolific choreographers and co-founder of the New York City Ballet], but very few people know about her South African roots – that she was trained here in South Africa. Our archive holds the record of that.

When I was a young dancer, my ballet mistress was the dancer, Dianne Richards. And, similarly, very few people know that her work began in Zambia, or about how she came to Johanneburg in the 40s and 50s, and what motivated her link to the London Festival, where she became a celebrated ballerina who toured around the world.

Our archival team includes Professor Elizabeth Triechaardt (former director of the School and current head of Cape Town City Ballet), Dr Eduard Greyling (former principal artist in the City Ballet company and academic at the School), Sharon Friedman (who introduced contemporary dance to the School) and music librarian Julie Strauss. I am in weekly contact with these individuals, who are a living repository of dance history, asking them: ‘Who is this in this picture? What was happening here? What date was this? Why did we do this and not that?’

We’re dealing with an extremely fragmented collection, but together, we’re trying to bring all the threads together to get the images into chronological order, build up the metadata, and generate a systematic way of looking at all the material. So that if, in 15 years time, a new researcher wants to trace any number of developments relating to shifts that went on at the School at different times, the raw material and source data will be readily available.

Eduard has been the driving force behind a parallel oral history project. About 15 to 20 years ago, he started interviewing various members of the dance community about the productions they’ve been involved in, their teaching processes… And those recordings have all been digitised.

‘Important biographies need still need to be written. We don’t have biographies that cover Spanish or African dance processes, for example. We only have one book introducing dance-teaching methodologies… Our hope is that the archive will generate new dance research material.’

The History of Ballet in South Africa, the only large seminal text on the subject, was written by Marina Grut, a former dance historian at the School, in the 1980s, but since then there has been no other book. Many of the images published in that book are from original photographs, which are part of this archive, but there are so many more.

In recent years, Sharon Friedman edited the book, Postapartheid Dance: Many bodies, many voices, many stories (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2012) , and many of the authors are based here at the School. But there is so much work still to be done. Important biographies need still need to be written. We don’t have biographies that cover Spanish or African dance processes, for example. We only have one book introducing dance-teaching methodologies… Our hope is that the archive will generate new dance research material.

The intention is to create a resource base that allows the new generation of dance researcher to be able to access the source data. The archive is housed right here in the dance department, and undergraduate students are invited to dip their toes in to it see what it is all about – their Honours and Masters projects could be coming out of there. They don’t need to be looking to some external case study elsewhere. It’s right here under their noses. We’re working in anticipation of the fact that, in ten years time, we are going to have a range of dance researchers in our country, who need to be able to go to this archive and find the material they’re looking for.

Gerard Samuel has been the Director of the School of Dance at the University of Cape Town since May 2008, and is a lecturer in Performance Studies and Dance Teaching Methodology. A professionally trained ballet dancer, choreographer, and former arts administrator of The Playhouse Company, he holds a Master's degree in Drama and Performance Studies from the University KwaZulu-Natal. He is also a pioneer of disability arts and integrated arts projects in Durban, South Africa, and in Copenhagen, Denmark, with his LeftfeetFIRST Dance Theatre. His research interests lie in the intersection of disability arts, and contemporary dance and performance.

Gerard Samuel has been the Director of the School of Dance at the University of Cape Town since May 2008, and is a lecturer in Performance Studies and Dance Teaching Methodology. A professionally trained ballet dancer, choreographer, and former arts administrator of The Playhouse Company, he holds a Master's degree in Drama and Performance Studies from the University KwaZulu-Natal. He is also a pioneer of disability arts and integrated arts projects in Durban, South Africa, and in Copenhagen, Denmark, with his LeftfeetFIRST Dance Theatre. His research interests lie in the intersection of disability arts, and contemporary dance and performance.